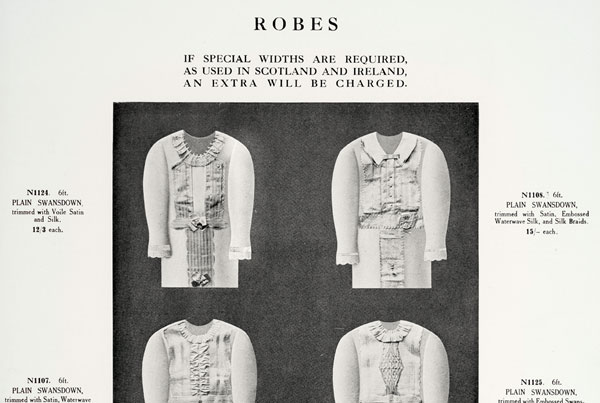

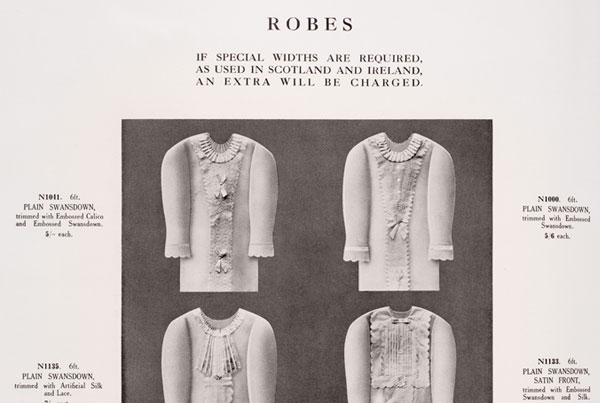

The Coffin Maker, Undertaker & Funeral Furnisher

In Britain’s urban areas, there was a split between the three funeral trade divisions – the coffin maker, undertaker and funeral furnisher. In the rural areas, the coffin maker was usually the local carpenter, who was also the resident cabinet maker. The two trades were ‘one and the same’ as a coffin was viewed as just another form of cabinet, put to an alternative use. Undertakers were usually only found in towns and cities, where the pomp and ceremony demanded their services in ‘undertaking’ all of the arrangements for a ‘respectable’ funeral.

Funeral Furnisher in demand!

They were the next step up in the hierarchy and were called into demand for the middle class funeral. For those funerals that demanded even more of a display – notably for the upper class families – only the funeral furnisher would do, although they would attend to middle class households as well, provided the bill could be paid. Funeral furnishers were at the top of the funeral trade, and could coordinate even the most important funerals for those at the highest levels of society.

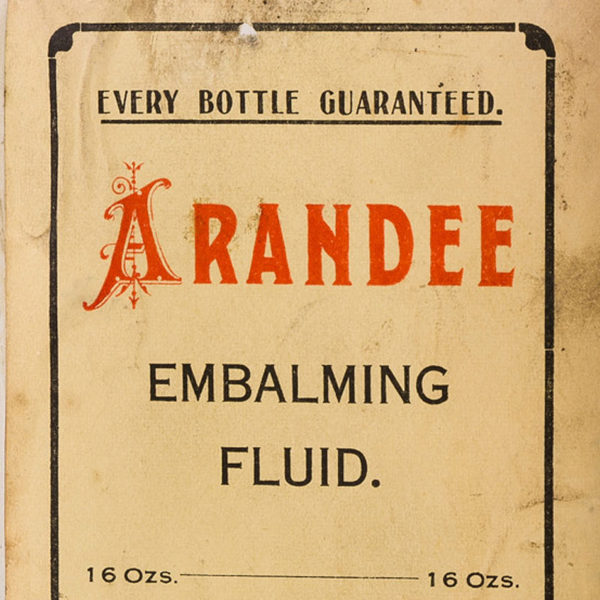

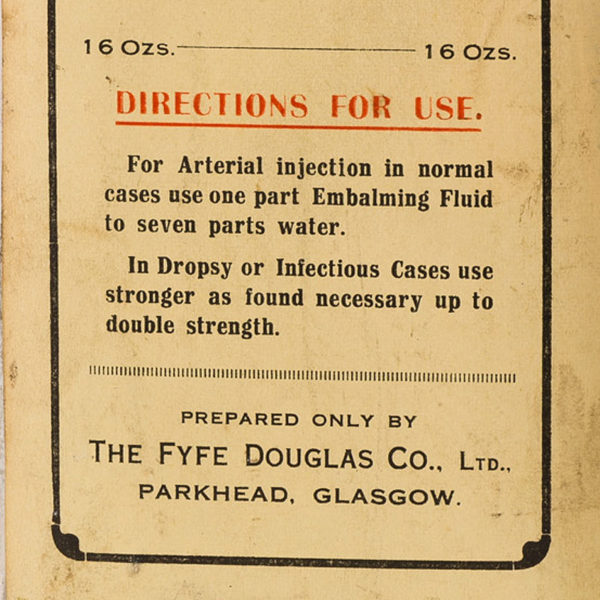

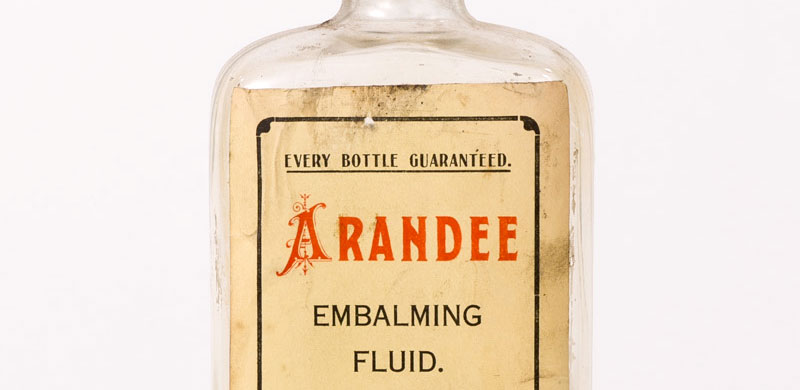

360° View of an Embalming Fluid bottle

Use the play button to rotate the object automatically, or alternatively you can drag the item with the mouse or your finger to move it around.

This item is in the following Themes:

Preserving the body

Although embalming started to gain major recognition within the funeral industry by 1900, J H Kenyon’s records show that only six embalments took place in that year, with just 56 by 1902. Prior to this, the only form of preservation was the ice chest and later, dry ice, which were frozen blocks of carbon monoxide. Dottridge Brothers of London marketed a product called ‘Drikold’ which had a temperature of 110f below zero. Although non-invasive, the downside was that blocks only lasted 24 hours. Embalming was therefore the only real alternative to preservation, but it didn’t gain popularity until after the 1950s, and was only used in extreme circumstances such as the Salisbury Rail Disaster of 1906, in which many of the dead were Americans, so had to be repatriated.

History of Embalming

The Americans were the pioneers of making embalming accessible. Although practised in Britain from the late 18th Century, it was the American Civil War that gave it greater exposure and made it commercially available. The bodies of the battle dead were embalmed ready to be transported back to their homes by Thomas Holmes, who was christened the ‘father of modern embalming’. He led the campaign, capitalising on methods developed by the French anatomist, Jean Gannal. This led to the opening of schools, but it was still considered a separate trade from that of the undertaker.

The turning point in terms of British history came in 1900, when the London-based funeral directors, Dottridge Brothers began offering classes at University College London, in association with the British Institute of Undertakers. The uptake was still minimal until after the First World War. However, most funeral directors didn’t have refrigerated premises until the 1950s, meaning that the funeral occurred within a few days after death, similar to Victorian practice. Embalming and refrigerated premises thus played their part in prolonging the period before the funeral.