Fashion designers have always looked to the past for inspiration. Dior’s ‘revolutionary’ New Look was inspired by the corseted waists and full skirts of the Victorian era whilst Chanel’s spring and summer 2019 collection was heavily influenced by the 1980s. The fashions of the 1980s were themselves inspired by the silhouettes of the 1940s.

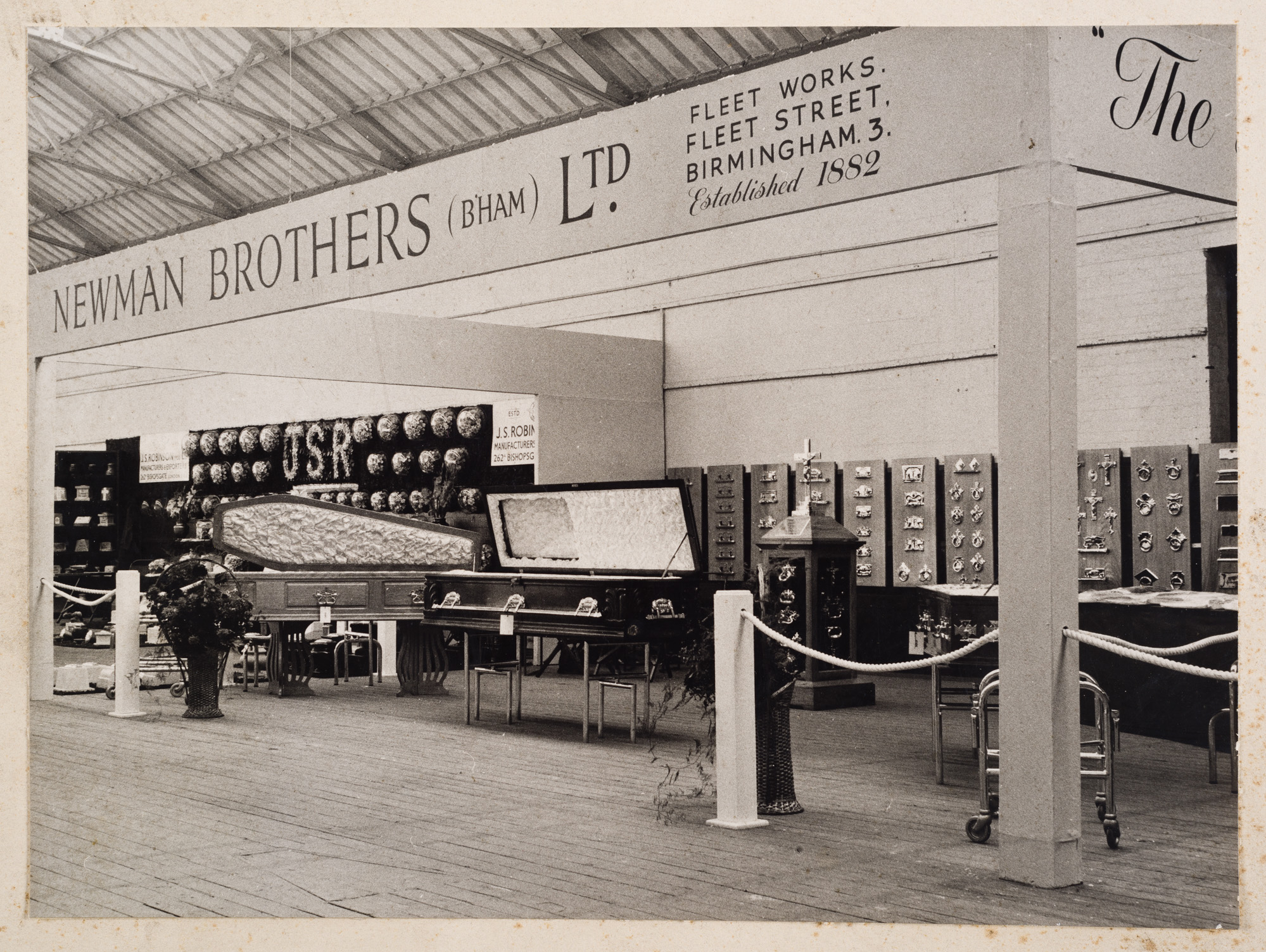

Newman Brothers’ Dead Fashionable SS20 collection is no different. With a reproduction of historic shrouds from the beginning of the 20th century we were limited to looking to the past for inspiration.

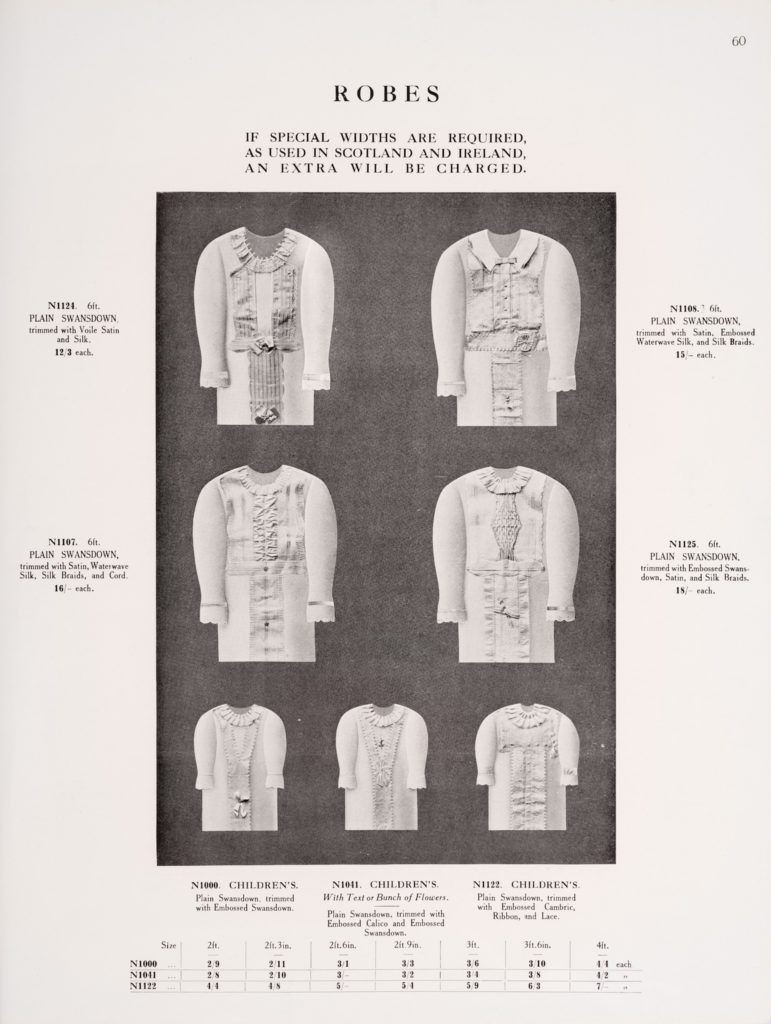

The Coffin Works is fortunate to be in possession of a number of shrouds dating from the 1970s onwards. Artist interpretations from the surviving trade catalogues provide the only evidence we have of what Newman Brothers’ shrouds looked like prior to that.

Nobody seemed to hold on to unsold shrouds left over after funeral businesses closed down. Although many people would be superstitious about wearing shroud material, some of those shrouds might have been bought up for their fabric which would make them no longer available for study. Shrouds sold to rival businesses would likely have been put to their original use and therefore also unavailable for study.

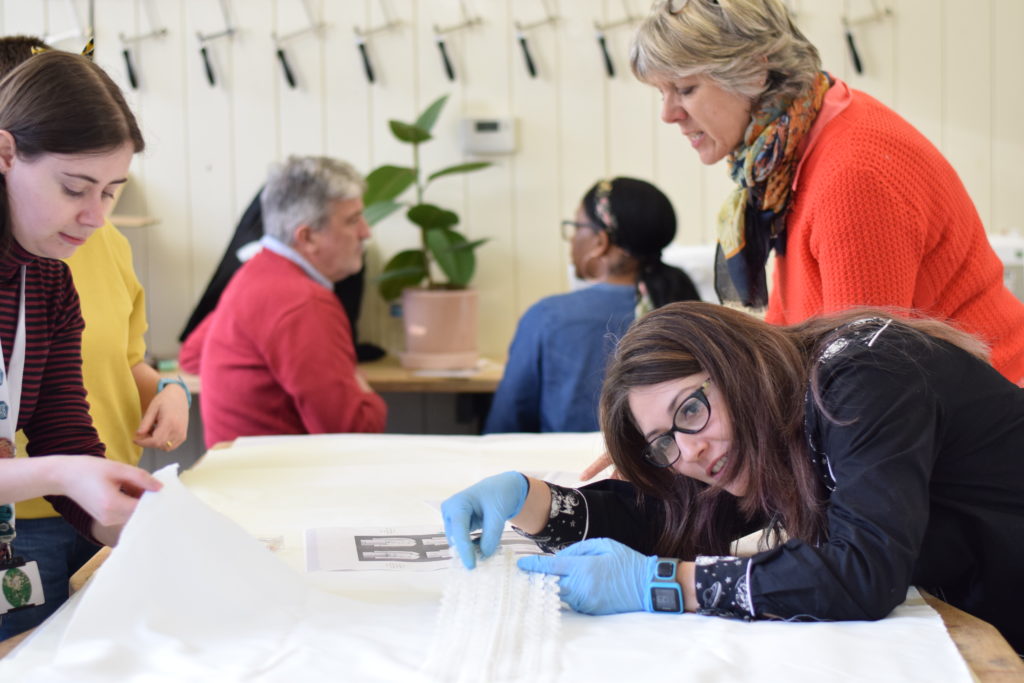

Thanks to Joyce Green’s foresight, when Newman Brothers finally closed its doors the contents of the buildings were retained for use within the museum. Museum Manager Sarah Hayes was keen use the shroud collection to tell stories about burial and funeral poverty. Thanks to funding from the Arts Council, Sarah was able to gather a group of volunteers. Working with Janet Gray from Feed My Creative the group would try and reproduce the missing shroud collection. The designs would be based on hand drawn images of shrouds from the start of the 20th century.

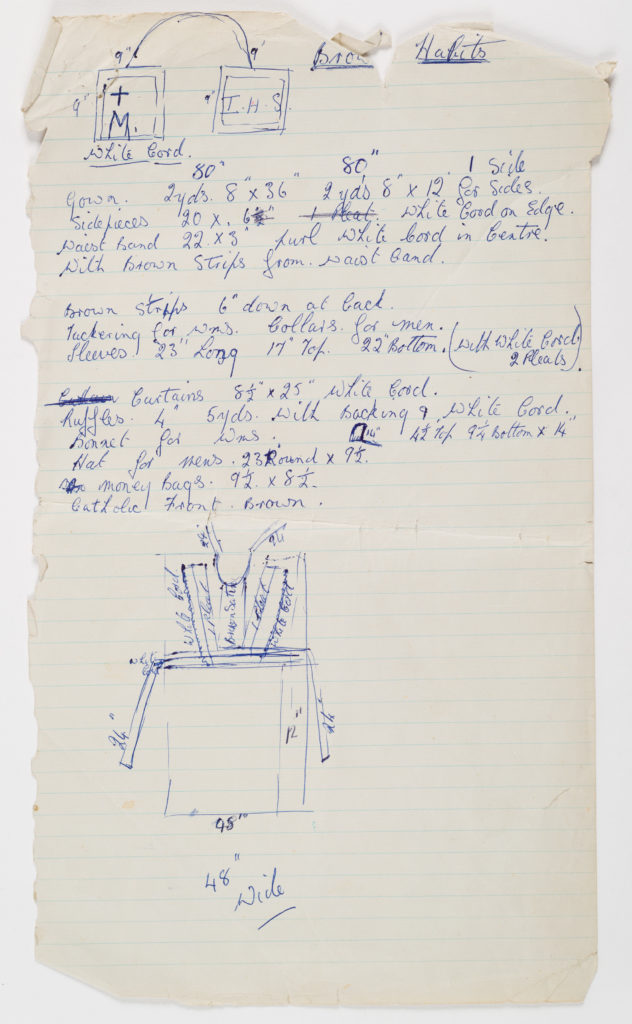

If you take 10 people, give them the same image and ask each one to deconstruct the design you’ll get at least 10 different interpretations. What colours are used? What fabric? The written descriptions beside the images give only one word descriptions. Where does the decoration begin and end, what are the dimensions of the various elements? First and foremost, how on earth was it was constructed? These were the problems the group undertaking the ‘Dead Fashionable’ project came up against.

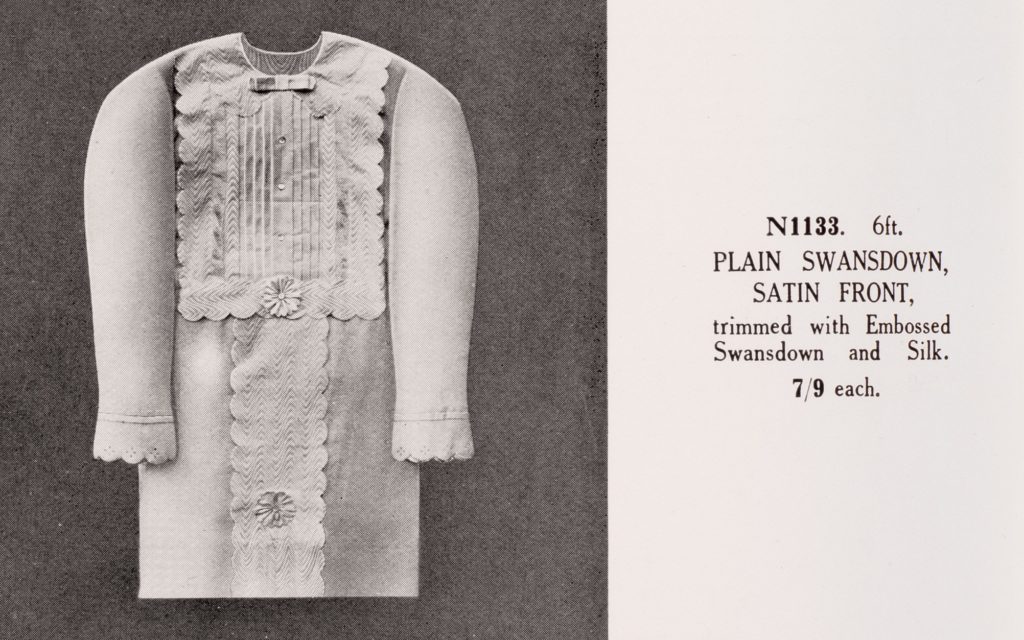

After batting ideas around, we decided to make a start on design N1133. The bow at the neckline indicates that this was a gentleman’s shroud and the price of 7/9 (about £444 in today’s money) would put it in the upper mid-price range. In 1925 it would cost about the equivalent of 22 days’ work for a skilled tradesman. A skilled tradesman today can earn between £100 – £300 a day. Using average earnings of £175 a day, which given inflation equates to £3850!

Swansdown was used for the main bodies of the shrouds regardless of shroud price as cost seems to have been determined by the type and volume of trim attached to them. So we used swansdown as our main fabric. It is a material which feels very similar to the brushed cotton flannelette that you probably remember from your childhood pyjamas. Given that the intention was to make the person look as if they were simply asleep, perhaps this choice is not so unusual. Swansdown is also used for babies’ clothes and could be symbolic of a return to the state of innocence associated with babies.

Using the existing modern shrouds as a template, we cut out a pattern. As the sleeves on modern Newman Brothers’ shrouds appeared to be cut as straight rectangles, we realised entire shroud could be cut from a single width of fabric resulting in the very minimum of waste. This lack of shaping may be because the sleeves were designed to slide on like gloves making it much easier to dress the body. Confusingly, the archive images seem to show a definite shaping to the sleeve. With no way of determining whether this was just artistic interpretation that helped sell products or whether they actually shaped the sleeve back then, we decided to follow the images and cut our sleeves wider at the top and taper down narrower at the wrist.

With the basic components of the shroud cut, it was time to establish how all the elements were put together.

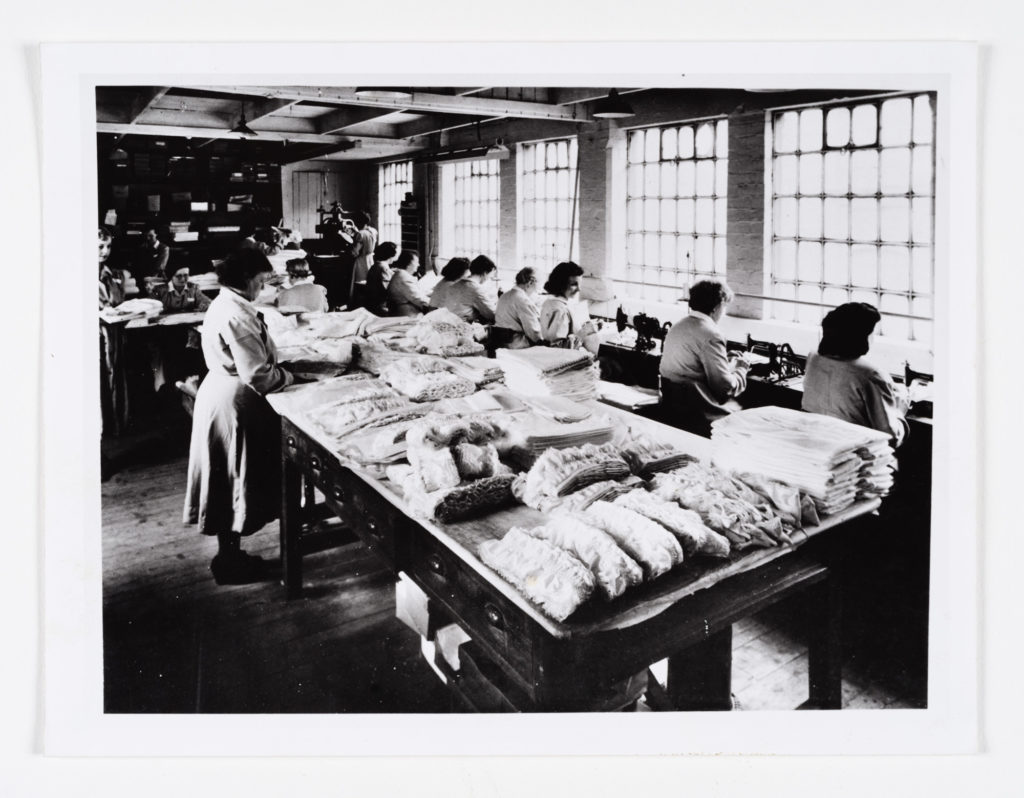

The first modern sewing machine designs were patented around the mid-1800s so by the time Newman Brothers open their doors it’s quite likely that industrial sewing machines were fairly commonplace. In the early days the firm focused on brass coffin furniture. Oral histories report that prior to the opening of the sewing room in the 1950s their shrouds had been made at home by a family of seamstresses, suggesting that Newman Brothers’ first garments were made entirely by hand. In 1912 the firm was advertising for seamstresses so presumably they created a dedicated working space and most likely had machines installed.

The current shroud sewing room was never labelled on the original plans so it appears to have been created with a flexible use in mind. The room gets plenty of natural light and is at a remove from from the dirty work happening in the side range, suggesting the old sewing room is the same room that the sewing machines sit in today.

The decorative bodice on gown N1133 seems to be a series of irregular raised puffs. To achieve this we experimented by gathering the fabric (running three rows of loose stitches down the front of the fabric and then the threads pulling up to produce gathers) then spreading the gathers out resulting in a puffed piece of fabric which appeared to match the illustration.

When replicating this on a different sewing machine with our best piece of fabric a volunteer, Charlotte, turned the sewing machine tension up to 9, which she believed it to be the loosest setting. She had in fact ramped the tension right up so that as soon as she started to sew, the tightness of the thread naturally pulled the fabric into gathers. Hey presto, a 3 minute task transformed into a 30 second one, a wonderful serendipitous life hack!

A delve into the museum’s collection uncovered rolls of pre-stitched trim and evidence that the girls used to stitch together rows of trim to create larger pieces to be applied to the shroud in one go.

The decorative bodice on gown N1133 seems to be a series of irregular raised puffs. To achieve this we experimented by gathering the fabric (running three rows of loose stitches down the front of the fabric and then the threads pulling up to produce gathers) then spreading the gathers out resulting in a puffed piece of fabric which appeared to match the illustration.

When replicating this on a different sewing machine with our best piece of fabric a volunteer, Charlotte, turned the sewing machine tension up to 9, which she believed it to be the loosest setting. She had in fact ramped the tension right up so that as soon as she started to sew, the tightness of the thread naturally pulled the fabric into gathers. Hey presto, a 3 minute task transformed into a 30 second one, a wonderful serendipitous life hack!

A delve into the museum’s collection uncovered rolls of pre-stitched trim and evidence that the girls used to stitch together rows of trim to create larger pieces to be applied to the shroud in one go.

In the oral history of Elizabeth Weaving, who worked in the shroud room in the 1970s, she remembers how the girls used to save time by cutting out multiple pattern pieces at once. She also recalls a trick they used to streamline the pleating of the material: “… we all had boards – we made them ourselves – with different markings on, and you would cut down the middle, cut across, open it up, on the machine, you would get, your ribbon and you would pleat it across the neck, after, you had already pinned your gathering part in.”

With such simple hacks, it’s easy to see how the girls could produce the gowns at such speed. Shrouds would never need to move meaning that corners could be cut. Rather than hemming the bottoms of the shrouds or finishing the seams, the fabric was edged using the large crimping machine which worked much like an industrial scale pair of pinking shears. The nipped edge hidden inside the sleeves or simply tucked under the body helped stop the fabric from fraying. Shrouds most closely resemble the hospital gowns worn during surgery and have open backs: another example of their design being led by the difficulty of fully dressing a corpse.