A Drab Thoroughfare with a Glamorous Name

An image of Fleet Street, 1953, showing a perspective that looks as though it includes Newman Brothers. ©Birmingham Daily Gazette

Street of Opportunity

A Visit to Fleet Street Birmingham

by Tudor Jones, 4th August 1953

In London, the name spells adventure: here it is synonymous with the enterprise that has sent Birmingham wares, famous for their quality, all over the world.

Fleet Street: the “street of adventure” they call it. But that is Fleet Street London. What of Birmingham’s Fleet Street? One can find adventure there too. In a short walk down its unrelieved drabness I found places where they made fittings for Oriental palaces and coffin-plates for kings; workshops that have hardly changed in 50 years, passing from father to son, and staying as examples of that early pride in workmanship and worth which made the name of Birmingham.

This little hive of industry lies only a couple of stone’s throws from the Town Hall. It runs along a stretch of the Birmingham and Fazeley canal. Once the street was a haunt of footpads. Police ventured into it only in twos and threes. Now it is a street of little stairways with surprises at the top.

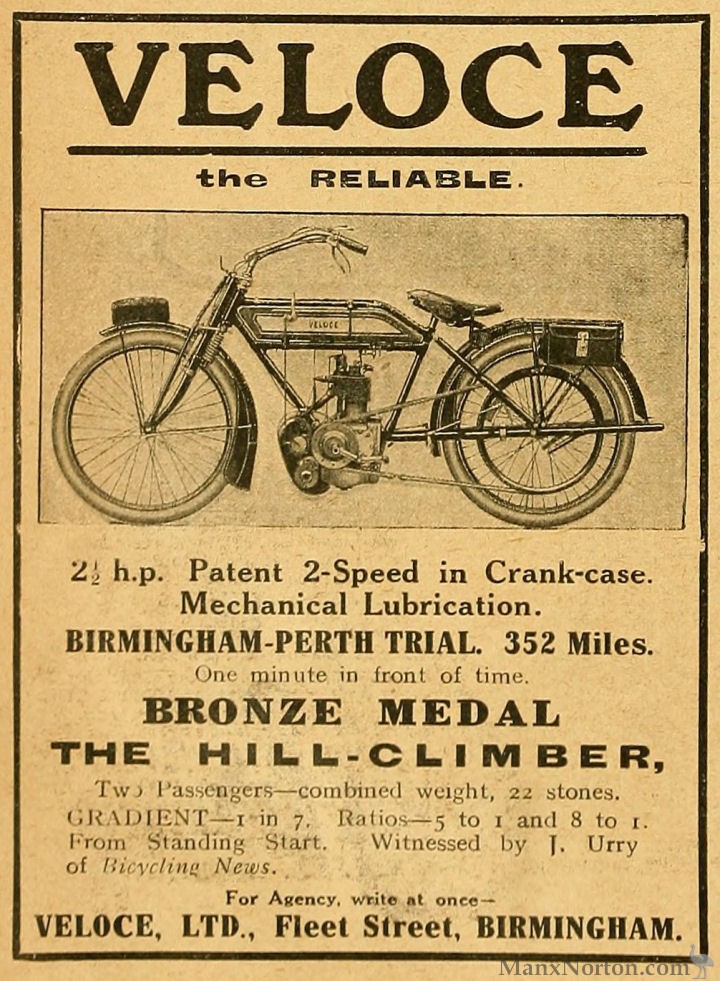

“Many millions a year are turned over in this street and nobody knows it,” said a man in the flight of offices at the top of the street. “Since we came into this little room 19 years ago our business has increased a hundredfold. A lot of people have started here — like Velocette motor-cycles, and Elkington’s the silversmiths. You can certainly call it the Street of Opportunity.”

The man speaking was Mr. E. W. Walker, of the Electric Construction Co. Ltd., of Wolverhampton, the firm which made an accumulator for the Birmingham Tramways Co. about 1890, and which now turns out machinery that no one else makes—for the Post Office, radar and the textile industry; and a firm in which workers share its profits.

An “Arabian Nights” story — about bathroom taps

“Look at Miss Callow here,” said Mr. Walker. “She started from nothing and now she’s overwhelmed.”

You find Miss Callow, a bouncing Lancashire lass, if you look in the offices of the Efficient Typing Service.

Veloce was the name of a type of motorcycle as well as the firm that made them from 1905 to 1971 and also in 1998. The brand name was later changed to Velocette.

Ten years ago her boss, an engineer from the south, joined up and announced to her that he would not be coming back. “Here’s a table, a filing cabinet, a typewriter and a telephone,” he said. “They’re all yours.” She deals with literary and learned manuscripts as well as with plain commerce. She comes and goes in a little car. Mr. Walker gave me the keynote to the street. “Good stuff pays,” he said.

In that same little room Miss Callow built up her business. Now her secretarial services are the cement in between all those busy firms from Leeds and Lincoln, Wakefield and West Drayton which have offices of her stairs.

At every door in Fleet Street I found this was the motto. At Cartwright’s — makers of millions of door-knobs, which go to every housing scheme in England and all over the world — Mr. G. Lawson and Mr. J. C. Northam almost became poetical as they praised the beauty of a partridge-wood door-knob on a cream door.

Mr. Howell Cartwright told me that his father started the firm in 1885 in Frederick Street, in the house where Washington Irving wrote “Rip Van Winkle.”

They started production in Fleet Street in 1900. From door-grips and policeman’s truncheons they moved with the fashion to wooden knobs, then aluminium plates and lever handles, then plastic.

Image of Miss Callow. ©Birmingham Daily Gazette

R. Cartwright and Co advertisements from 1951 and 1961. Note from the images, the address listed at the bottom of ‘fleet Street’. © https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/R._Cartwright_and_Co

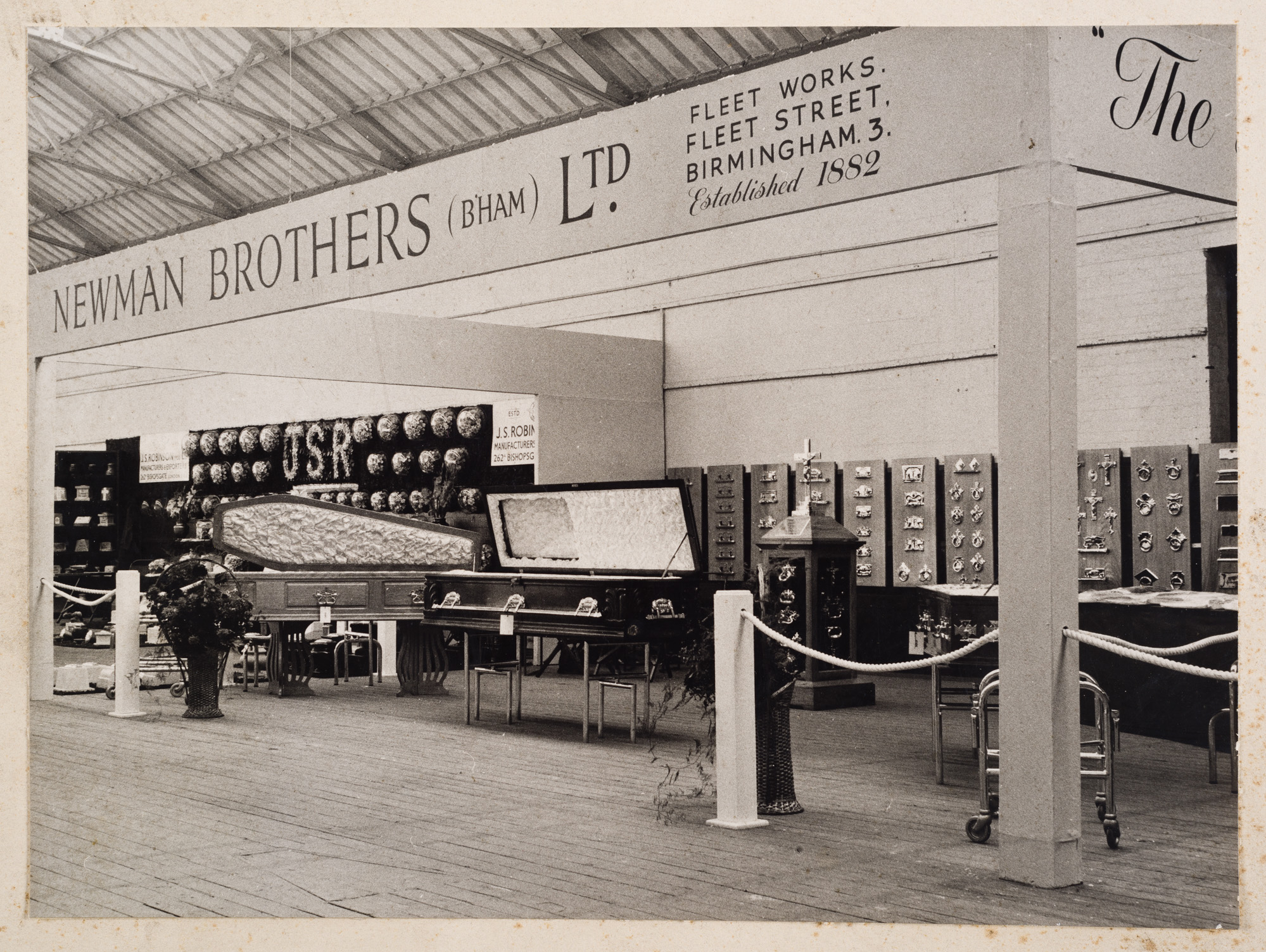

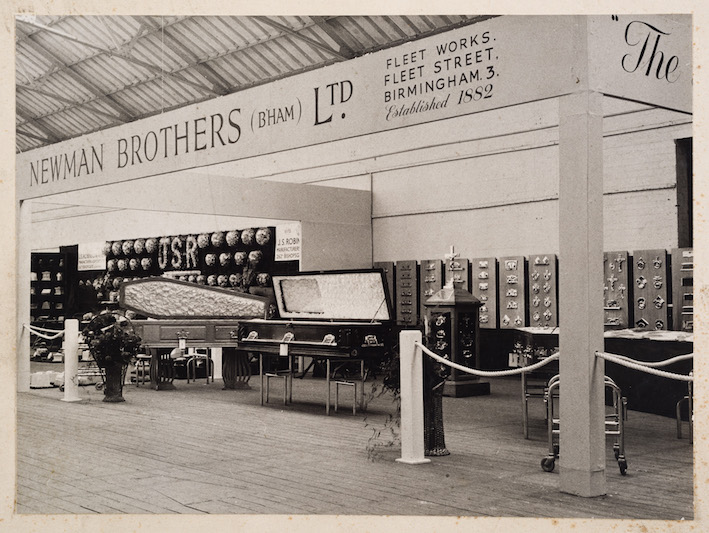

At the House of Newman I learnt that the making of coffin-furniture is a real Birmingham trade. “Of the 12 firms in Britain, ten are in Birmingham,” said Mr. J. V. Kellett, director. This would appear to be the first factory built in Fleet Street. It must also be one of the last using real brass, entirely hand-dressed and hand-styled.

‘The House of Newman’ was a form of branding for their products. This image is taken from a Blackpool trade exhibition in the early 1950s.

Young Michael Lane—university and Royal Navy— is in Fleet Street to look after the firm which his grandfather founded— W. Markes and Co. Ltd. “And I married a girl from a newspaper office in Fleet Street, London,” he said.

He showed me a display of solid, heavy, luxurious brass and nickel hot-and-cold water fittings; then took me away on a magic carpet.

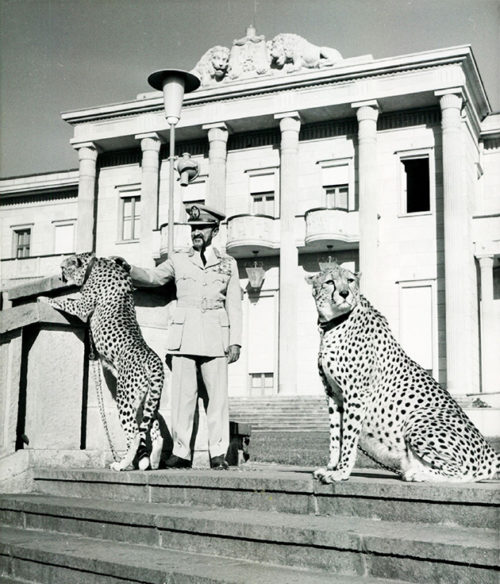

“Ex-King Farouk built a Summer palace on the lower Nile,” he said “and we made special fittings for it. We fitted up the Emperor Haile Selassie’s new palace at Addis Ababa, and the whole Bank of Shanghai building, the gem of the waterfront.

Image of Michael Lane. ©Birmingham Daily Gazette

“The Maharajah of Baroda had very elaborate bathroom fittings from here. His taps were eventually gold-plated and inlaid enamel and cost £200 to £300 each.” Hospitals paid for out of the Sheik of Bahrein’s oil royalties; hospitals in Eire built of the profits of the Irish Sweepstakes; laboratories at Harwell’s atomic energy establishment; a South American liner—these are some of the other enterprises which have resulted in orders for Fleet Street, Birmingham.

Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie, in front of the Jubilee Palace in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

It is modern business, but the Markes firm still uses old hand-lathes: and two of the craftsmen came in with Mr. Lane’s grandfather and the original William Markes. Three blind Poles were also working at the lathes — “they are first-class,” said Mr. Lane.

In another Fleet Street building—it was once an inn—Mr- J. C. Prince presides over the glass bevelling firm of Joseph Price and Sons, founded by his father. Their 1898 world of leaded lights, cart-lamps, cabs’ blue glass, fire-screens and overmantles has given place to bathroom tiles, cafe table-tops, cocktail bar fittings and glass for motor cars and window displays. But they still make glass for railway lamps. Mr. Herbert Pearsall, a worker with the firm for 50 years, links the two periods.

Another hand-workshop in the street is that of the Birmingham Envelope Co. Here again Mr. L. S. Caddy, the managing director, carries on a firm founded by his father. The business was started to make hand-folded envelopes, of which it still turns out millions a year, even in these days of mass production.

“We are a gang in this street,” was one of the remarks I heard. “We know each other and we can act together when need arises.” And it is, without exception, a “gang” interested in maintaining the street’s reputation for quality.

Here, as elsewhere, they complain that young people are not coming up to learn the crafts from the older men. But if ever Birmingham’s name for sound and solid workmanship goes down, it will not be the fault of the big little shops of Fleet Street.